Order Now

Available online and at your favorite booksellers

From author Elaine Weiss

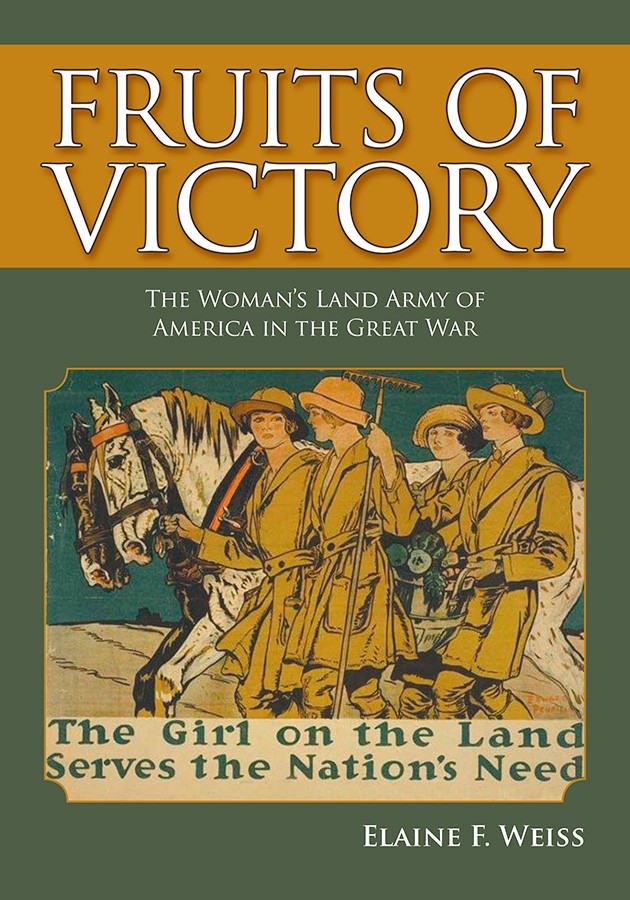

Fruits of Victory

Imagine a spunkier, and more controversial, Rosie the Riveter – a generation older, and more outlandish for her time. She is the “farmerette” of the Woman’s Land Army of America, doing a man’s job, in military-style uniform, on the rural home front during WW I.

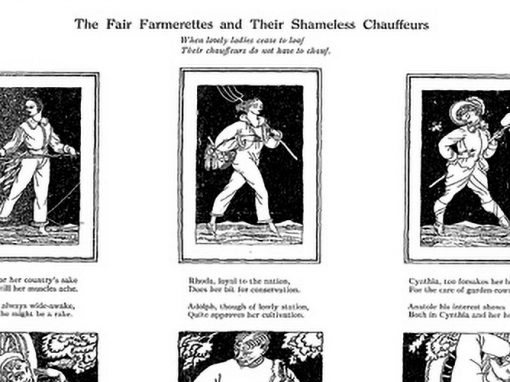

During the war she was the toast of Broadway, the darling of the smart set, a star of the wartime cinema newsreel, and highlight of the Liberty Loan parade. Victor Herbert and P.G. Wodehouse wrote songs about her, Rockwell Kent drew sly pictures of her, Charles Dana Gibson created posters for her, Theodore Roosevelt championed her, the New York Times wrote editorials about her, and Flo Ziegfield put her in his follies. And then she disappeared.

For ninety years the farmerette has been lost, totally and inexplicably forgotten, wiped from the national memory. Her story has never before been told… until now. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War by Elaine F. Weiss brings the lost story of the farmerette back to American history.

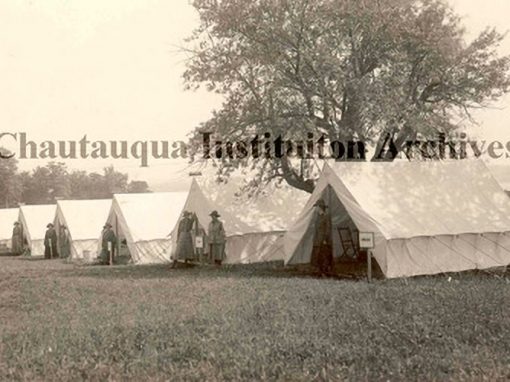

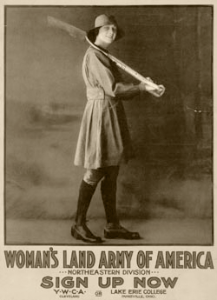

From 1917 to 1920 the Woman’s Land Army brought thousands of city workers, society women, artists, business professionals, and college students into rural America to take over the farm work after men were called to wartime service. These women wore military-style uniforms, lived in communal camps, and did what was considered “men’s work” – plowing fields, driving tractors, planting, harvesting, and hauling lumber. The Land Army insisted its “farmerettes” be paid wages equal to male farm laborers and protected by an eight-hour workday. These farmerettes were shocking at first and encountered skeptical farmers’ scorn, but as they proved themselves willing and capable, farmers began to rely upon the women workers and became their loudest champions.

While the Woman’s Land Army was deeply rooted in the great political and social movements of its day – suffrage, urban and rural reform, women’s education, scientific management, and labor rights – it pushed into new, uncharted territory and ventured into areas considered off-limits. More than any other women’s war work group of the time, the Land Army took pleasure in breaking the rules. It challenged conventional thinking on what was “proper” work for women to do, their role in wartime, how they should be paid, and how they should dress.

The WLA’s short but spirited life also foreshadowed some of the most profound and contentious social issues America would face in the twentieth century: women’s changing role in society and the workplace, the problem of social class distinctions in a democracy, the mechanization and urbanization of society, the role of science and technology, and the physiological and psychological differences between men and women.

Weiss delves deeply into an overlooked aspect of life on the American home front during World War I, which coincided with the peak of the woman’s suffrage movement. The war caused a sea change in opinions about what was men’s and women’s work in many fields, including agriculture, just as food riots erupted in 1917 as people rebelled against rising prices, some of which quadrupled during the war. Weiss surveys the spectrum of individuals who put American women to work on farms across the country at this critical time, including Barnard College’s Virginia Gildersleeve and Mount Holyoke’s Mary Woolley, and provides fresh gender history as she highlights the contribution of many seldom-considered feminists. She also stresses the long-term contribution women made to labor history during this time by insisting on an eight-hour day and exposes conflict within the women’s movement over how to address war-related issues and civilian farming efforts. Weiss’ excellent work of cross-disciplinary scholarship offers readers a unique look at how WWI changed society.

Bravo to Elaine Weiss! She has rescued a fascinating chapter of our history from undeserved obscurity and tells the story of the Woman’s Land Army of World War I with undeniable verve.

Elaine Weiss has written an important book on an overlooked subject. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army in the Great War covers the virtually unknown story of the “farmettes” who joined American’s land army to feed the nation during World War I. This engaging account makes not only good reading, but also contributes to our understanding of both women’s history and the home front during the war.

Weiss, who has written for such publications as the New York Times and Harper’s, chronicles the largely forgotten history of the Woman’s Land Army (WLA), a group of women in the United States who left their homes and college dorms in droves to volunteer when American involvement in World War I called young men from the fields to the trenches of Europe. Weiss shows how these “farmerettes” faced an uphill battle, as they were often met with disdain by shorthanded farmers and Washington politicians who did not feel the situation was dire enough to warrant hiring women to do men’s work. WLA architects, many of whom earned their stripes in the suffrage movement, developed a blueprint for managing a group anywhere in the United States, and they were able to secure wages-and an eight-hour workday-equal to their male counterparts. The group was disbanded after the war, but the farmerettes helped pave the way for women working during World War II. Weiss effectively chronicles the birth of the WLA movement and the dedicated women behind it. Recommended for both scholarly readers and interested history buffs.

Weiss plows through a wide variety of primary sources and produces a bumper crop of determined women, stubborn men, telling anecdotes, and rich details, all part of a surprising and surprisingly moving story of mobilization and organization, patriotism and sexism. The army of “farmerettes,” drawn from the classrooms of the “Seven Sisters” and urban factories, who came together as “soldiers of the soil” to harvest everything from cherries in Michigan to cotton in Georgia and the women who recruited, trained, and championed them leave an indelible imprint in this well-told tale of the remarkable effort of American women to feed a nation at war.

EXCERPTS

Order Now

Available online and at your favorite booksellers

Notes

I once knew a real farmerette, and I happened upon the story of the Woman’s Land Army in her farmhouse in the hills of Vermont. Her name was Alice Holway and she was almost 80 years old when I met her. She loved to tell stories of her service in the Land Army, she was very proud of having “done her bit” during the Great War. I duly jotted down her tales, but I could not find any information about this Land Army. There was nothing in the local library, no mention in the history texts, no trace. I thought about it over the years, would make a stab at finding something, then give up in frustration. (This was the era before the internet.)

Now I understand why I could not find any mention of this fascinating, but forgotten, episode in American history: until I wrote Fruits of Victory, there was no complete account of the Land Army in WWI, anywhere.

But once I began digging deep enough, I found that the Land Army story in WWI is there – if you don’t mind getting dusty. It is hidden in primary documents scattered around the country, tucked in local libraries and great university collections; it is in the files of government bureaucracies, under the domes of state archives buildings, and in the musty basements of tiny historical societies. It is there, in newspaper morgues, in women’s club minutes, in college scrapbooks, garden club records, war work transcripts, suffrage publications, and in piles of handwritten letters. My research took me around the U.S. and across the sea to England.

Scores of librarians and archivists around the country have been pleasantly surprised, and truly excited, to find Woman’s Land Army documents in their possession. I am truly grateful for their help and their enthusiasm. They enjoyed some surprises, too: The archivist of one great southern city was truly stunned when I showed him a photograph of the Woman’s Land Army of Augusta, Georgia at work picking cotton in 1918. “I can hardly believe it,” he said of this scene of socially prominent white women stooping in the cotton fields of Georgia. “That simply was not done.” But it was done by the Land Army in Augusta in that wartime summer – just one of many instances when farmerettes flaunted social conventions in the name of patriotism.

But the WWI farmerette had become a weird ghost – her image was still apparent, but with no identity or context: The most famous Woman’s Land Army recruitment poster, painted by Herbert Paus in the classic WWI style, is again popular today and can be purchased from any number of art galleries or historical poster merchants online. It’s a terrific poster, and probably graces many a modern wall, but I doubt many of the proud owners displaying it have any idea of what the poster means, what the Woman’s Land Army was, or why those cute farmerettes in the picture are wearing uniforms and carrying bushel baskets and flags. Coffee mugs, T-shirts, even boxer shorts and (gasp) thongs bearing the image of the Paus poster farmerettes can be purchased online. It’s a wonder.

In Fruits of Victory, I’ve tried to bring that farmerette, a sassy daughter of her turbulent times, back to life, piecing her together from fragments scattered around the nation, hidden in obscure places, buried in plain sight. I’ve attempted to place her back in the sweeping narrative of America at war, of a nation in transition, of women on the threshold of suffrage and modernity. I’ve tried to restore her voice – singing, reciting poetry, arguing, complaining, speechifying. And, of course, to recapture the excitement of her unusual call to service – “The Girl Behind the Plow Behind the Man with the Gun,” the woman scything for Uncle Sam to win the war. The farmerette deserves to reclaim her place in history. I hope you enjoy reading about her.